At AISP, we help government agencies, university partnerships, and community initiatives share and integrate data to improve outcomes.

Updated resource now available!

AISP’s Introduction to Data Sharing & Integration was originally published in 2020. In 2025, we made a comprehensive revision to this resource, updating our guidance and examples throughout.

This resource is intended to help public sector data sharing partnerships and community initiatives build a foundation for sustained data sharing and use to improve lives. It now includes sections on finding your shared purpose, building your team, weighing risks and benefits, and getting started with the five quality components of Integrated Data Systems (see below).

Access the updated resource here.

Data Sharing vs. Data Integration: What’s the Difference?

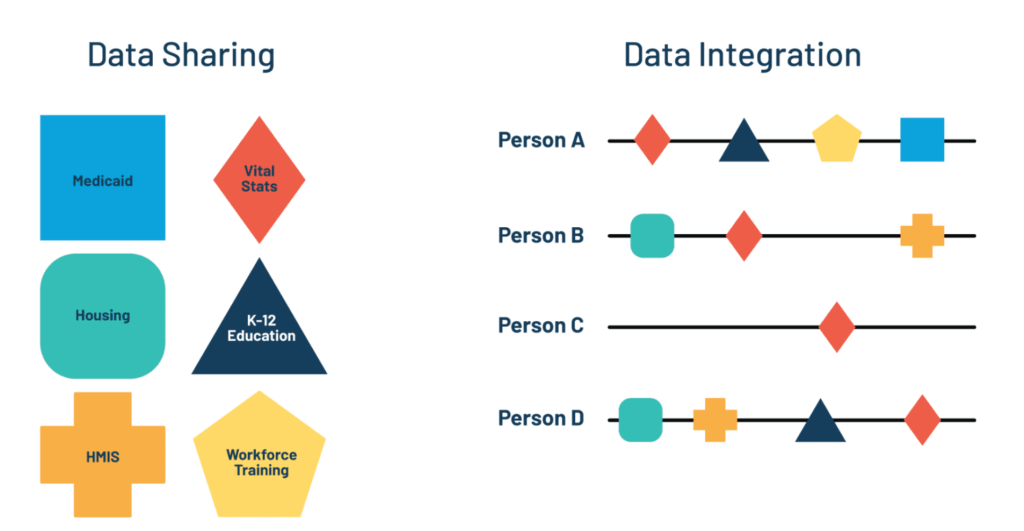

DATA SHARING is the practice of providing partners with access to information (in this case, administrative data) that they cannot access in their own data systems.

DATA INTEGRATION is a more complex type of data sharing that involves record linkage, which refers to the joining or merging of data based on common data fields.

Benefits and Risks of Data Sharing and Integration

Done right, data sharing and integration efforts all communities and decision-makers to better:

- Understand the complex needs of individuals and families

- Allocate resources where they’re needed most to improve services

- Measure long-term and two-generation impacts of policies and programs

- Engage in transparent, shared decision-making about how data should (and should not) be used

Data sharing also comes with serious limitations and risks, so each potential use of data should be carefully considered. For more on engaging diverse voices and assessing the risk vs. benefit of data sharing through participatory data governance, see A Toolkit for Centering Racial Equity Throughout Data Integration.

Purposes & Approaches to Data Sharing

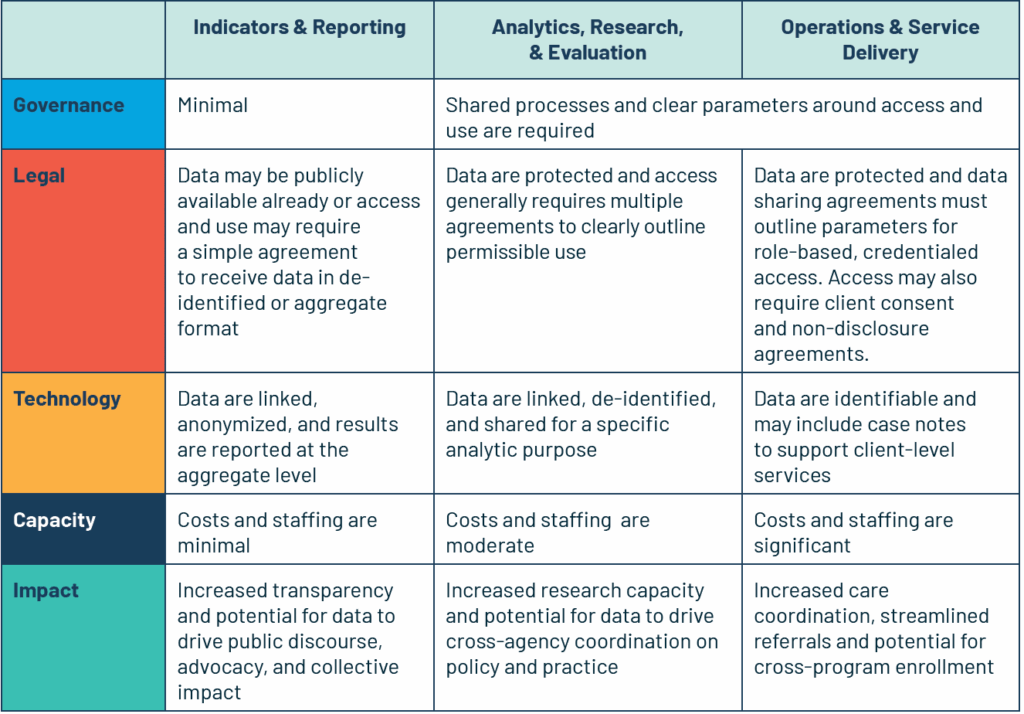

As you get started, it is important to distinguish between three core purposes for data integration, each with unique implications that drive the design of systems.

Purpose: Fullfills cross-agency planning and reporting requirements, and makes program outcomes more transparent

Audience: Agencies, policymakers, the public

Example: A collective impact initiative wants to report on a set of common indicators through a publicly available dashboard

Purpose: Enables detailed cross-agency analyses of long-term outcomes of service utilization

Audience: Researchers, evaluators, research and planning staff

Example: City agencies want to understand how outcomes vary for clients based on demographic characteristics and participation in multiple programs

Purpose: Facilitates sharing of detailed cross agency data to improve service delivery and care coordination

Audience: Case workers, service providers, executive leaders

Example: County agencies want to link their data in near real-time to enable coordination for improved delivery and increased quality of care

Key Considerations Across the Quality Framework

Learn more about how each of these are operationalized across the AISP Network by exploring our AISP Network Survey page. To learn more about these five key components, visit Quality Framework for Integrated Data Systems.